SAHUARITA, Ariz. (KGUN) — A strange white sludge that flowed through washes in the Entrada neighborhood during last year’s monsoon is again raising alarms, after similar material surged down the same path this fall, hardening wash sand to the texture of concrete.

Residents say the repeated incidents show the state has not properly investigated the source — and they’re urging the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality to expand testing and take stronger enforcement action against the Cimbar Resources mining operation upstream.

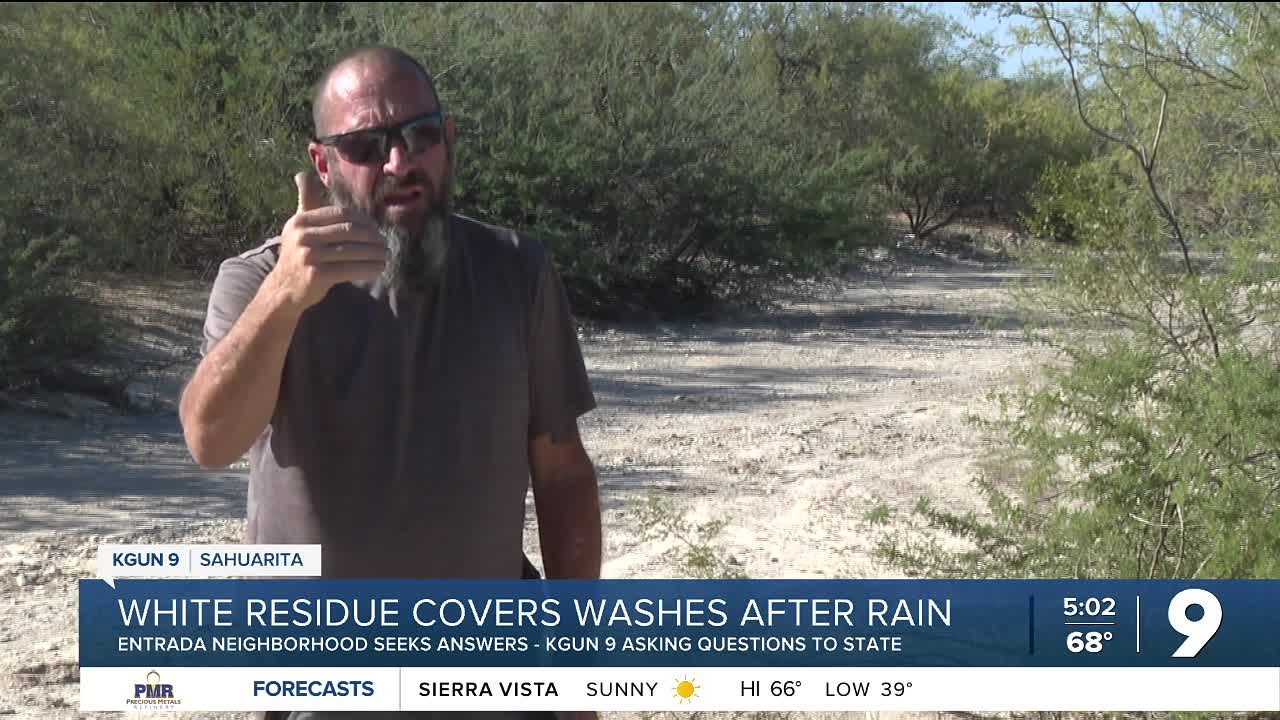

Entrada resident Chris Naylor remembers the moment he first saw the material on August 19, 2024. “This wash right here flooded, and it was the only one in the neighborhood,” he recalled. “When I started looking, I noticed there was a white material. It was like a sludge-like material, and it settled in, like this right here.”

PDEQ inspectors arrived three days later and documented the dried substance in the wash, identifying it as calcium carbonate, the same mineral processed at the Cimbar quarry. Because the material did not reach federally protected waterways, the agency determined it did not have legal authority to issue violations.

But for residents like Naylor, that explanation doesn’t capture the full picture.

He says Pima County’s PDEQ investigator traced the flow all the way from Cimbar’s property line. “She determined that it came from the property line at Cimbar all the way down through our neighborhood, and it went eight and a half miles from the mine,” Naylor said.

Residents began asking what else, if anything, was in the material. ADEQ initially tested only for calcium carbonate and concluded that the substance was harmless. But Naylor says that limited testing didn’t match what neighbors were asking for.

“Of course, we started asking questions about what it was,” he said. “They told us it was calcium carbonate and nothing else. After six or seven months of prodding, they did some testing outside the neighborhood, then inside the neighborhood, and the report found that right at the entrance of the neighborhood, where the wash comes through, there was a slight elevation in arsenic. But we never got any more results in the neighborhood.”

That arsenic reading — 15 mg/kg, slightly above the state’s residential guideline — was taken at the edge of Entrada, not within it. ADEQ says the result is not unusual because arsenic occurs naturally in local soils, and that the lower levels found closest to the quarry do not point to mining as the source. But residents say that leaves unanswered questions.

“We never got any type of explanation,” Naylor said. “Supposedly, there were two [samples] done inside the neighborhood, but that didn’t show up in the report we were given.”

Many residents are also skeptical of the agency’s explanation of Cimbar’s stormwater permit status at the time of the 2024 discharge. ADEQ now says the company had permit coverage, but that the listed location was incorrect until it was corrected after the complaint. But Naylor says that wasn’t what investigators told him at the time.

“When she was doing her investigation, Cimbar was not permitted,” he said. “They were operating under the old company’s licenses, or whatever they had. So they couldn’t investigate.”

The issue resurfaced dramatically in October when remnants of Hurricane Melissa swept through the area. “This wash was almost back to normal, and now all that calcium carbonate, sludge, whatever it was, came through again,” Naylor said. “And it goes the same distance it went before.”

The repeated flow has deepened frustration not only in Entrada but also among neighboring communities. Corona de Tucson resident Cathy McGrath said she first learned about the incident from neighbors. She fears that the incident is indicative of potential future issues relating to Hudbay’s Copper World project, which looks to start operating in 2029.

“Something happened in the neighborhood five miles from us,” she said. “They had a white substance come flowing down. It looked like cement when it hardened. It embedded itself all over the neighborhood, and we wondered to ourselves, what if that were Copper World?”

McGrath says ADEQ’s limited testing eroded trust. “ADEQ was in charge, and they had samples, but they didn’t test them. They said it was calcium carbonate, and it was harmless,” she said.

When she and others eventually obtained the test report, McGrath said they found that ADEQ tested only for calcium carbonate — nothing else. “It’s kind of like you’ve got a bunch of sick people in a paint factory, and you test for paint.”

After pressure from residents, ADEQ agreed to return in May 2025 for broader testing. But rather than retest the six original samples, the agency tested only three — all outside the neighborhood. The sample farthest downstream, at the edge of Entrada, is the one that showed elevated arsenic.

“When they tested for calcium carbonate, we started bothering them about coming back and doing a full-spectrum test,” McGrath said. “But instead of retesting the six samples they told us they were going to retest from before, they only tested three, and they stopped at the edge of the Entrada neighborhood.”

She says the solution now is obvious: “I would like to see ADEQ come out and test once and for all. If they think the arsenic is naturally occurring in the soil, then they should test the substance and then test two clean soil samples outside the wash area to determine that it’s a fact.”

Residents have also raised broader concerns about how the state will regulate future projects, pointing to the proposed Copper World mine in the same mountain range.

“All of this is a precursor of how they’re going to manage the copper mine once that comes online,” Naylor said. “If they can’t handle a simple calcium carbonate mine and what they put out, how are they going to maintain or enforce or regulate anything coming from a copper mine?”

ADEQ maintains it followed the law, acted quickly, and went beyond what is required by inspecting the facility, ordering improved stormwater controls, and conducting additional testing.

The agency issued a new correction notice after the October 2025 storm, requiring Cimbar to document stormwater “visual assessments” that were missing from the facility’s records.

But residents say that without comprehensive neighborhood sampling, the investigation remains incomplete — and the community remains uneasy.

“I’d just like to see this stuff stop coming down the wash,” Naylor said. “Let ADEQ do their job and keep it on the property.”

——

Joel Foster is a multimedia journalist at KGUN 9 who previously worked as an English teacher in both Boston and the Tucson area. Joel has experience working with web, print and video in the tech, finance, nonprofit and the public sectors. In his off-time, you might catch Joel taking part in Tucson's local comedy scene. Share your story ideas with Joel at joel.foster@kgun9.com, or by connecting on Facebook, Instagram or X.