DENVER, Colo. -- In Vitro Fertilization, or IVF, is often a woman, man or couple’s last chance to have a baby naturally, but that chance often comes at an extraordinary cost.

Doctors estimate the average cost of one cycle of IVF treatment can run anywhere from $15,000 to $20,000, but with no guarantee of pregnancy, many patients must go through multiple treatment cycles and end up paying much more than the average cost.

Maternity and newborn care are considered essential benefits under most health insurance plans, but infertility care is not. Coverage runs the gamut and most insurance companies do not cover IVF, or the drugs and hormone injections needed, leaving families with tens of thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket costs.

Other families are forced to take out high-interest loans or worse decide they can’t afford to try.

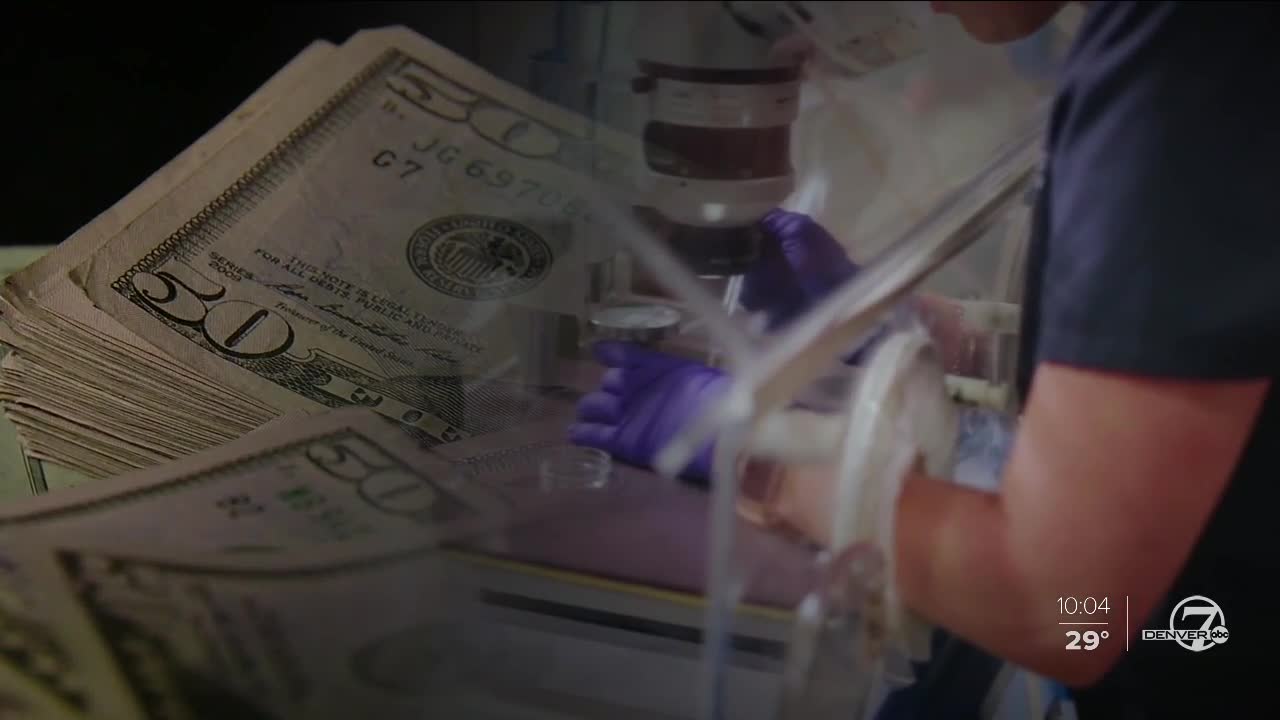

KMGH found the high cost of IVF medications is pushing everyday Colorado families into illegal black market dealing where people are buying and selling fertility drugs online for a fraction of the cost.

Colorado women turning to the black market

"They are much less on the black market," said Kelly, a Colorado woman now selling her leftover fertility drugs on the black-market website.

Kelly knows it's illegal to sell her leftover medication on the black market, but with no legal way to recoup the $800 she spent on drugs she no longer needs, she decided to take the risk.

"After you spent $35,000, getting $600 of $800 back sounds great. It's something to hold on to," she said.

Kelly and her husband, Aaron, only wanted to use their first names because of the risk they are taking by selling their leftover fertility drugs. They also wanted to share their raw, intensive IVF journey and why they're doing it.

"October of 2018 is when we pull the goalie and started trying to grow our family," said Kelly. "And by March of 2019, nothing had happened."

The couple made the decision to get tested and the first test came back with difficult news.

"That's when the doctor literally told me that you're not going to have kids, you don't even qualify for IVF. It's not going to happened," she said.

The couple was determined to have a baby naturally and wasn't giving up.

"When someone gives you just catastrophic news, you get a second opinion," said Kelly.

They found another doctor willing to do IVF treatment, which she would quickly learn came with boxes of drugs, vitamins, and injections.

"Physically, I felt fine. It was the emotional toll, I think, that was bigger," she said.

None of her prescriptions and protocols were covered by insurance.

"Aaron and I have spent $35,500, and if I get pregnant it's going to be another thousand," said Kelly.

Doctors ended up prescribing Kelly more fertility medication than she needed, which left her with expensive drugs and no way to recoup what she paid. That's what she said led her to look for a way to sell them.

"I just googled it. My nurse actually told me you can try and sell them," she said.

Her simple online search took her to a Canadian website where the black market for fertility drugs is thriving.

KMGH found drugs up for sale all over Colorado and across the country.

When one prescription of a well-known injectable fertility drug, called Gonal-F, costs $800 at the pharmacy and can be bought for half that price on the online black market, some women are willing to do anything to get the drugs at that price.

The meds are so in demand, posts only stay up for a few days.

Fertility doctor warns of black-market risk

"Basically, [it’s] forcing people to make these unfortunate choices," said Dr. Alex Polotsky, Director for University of Colorado Advanced Reproductive Medicine, who is internationally recognized for success of IVF. "As much as we'd like to decrease the cost, that's not the safe way to do it."

Polotsky said going in blind and buying from someone a patient doesn't know comes with a big risk, especially since many fertility drugs need to be refrigerated to work.

"There's definitely folks who can overdose on fertility medications and potentially have life-threatening complications," he said.

Polotsky said the issue with the cost of medications is due in large part to the lack of insurance coverage.

"In my eyes, and many others, it signifies a lack of support of women's health," he said.

IVF success story

Chava and Eric Riemer are an IVF success story.

"We definitely tried hard for him," said Eric Riemer of his now-two-year-old son.

The Denver couple spent nine long years trying to get pregnant, costing them upwards of $200,000.

The Riemers had some help with the cost through her insurance and a paid study into which they were lucky to be accepted, but still had to pay plenty out-of-pocket.

"We had two failed cycles and he was the third cycle," said Chava Riemer.

Life with their two-year-old son Zeke is now full of trucks, tools, and energy.

The couple did have leftover fertility drugs, but never explored selling them on the black market.

"The real stuff was bad enough. I wouldn't want to take a chance it not being the real one, but I definitely understand wanting to save some money," she said. "We wondered whether or not it was really the actual cost or how much it was inflated.

Kelly and Aaron find out if they're pregnant

"I don't think about it much, but literally every single night I wake up around 3:00 a.m. or 3:30 a.m. dreaming of pregnancy tests every night, and most nights I can't fall back asleep," Kelly told us back in early February two weeks before they were scheduled to find out if the treatment worked and whether they were pregnant.

Kelly described her IVF treatment as an emotional roller coaster filled with twice daily injections, way too many hormones, and plenty of anxiety but she was also motivated to do whatever it took to have their own baby.

The couple recently learned their IVF was successful and they are pregnant with a baby girl and said they couldn't be happier.

This story was originally published by

Jennifer Kovaleski at KMGH.